Hey trail runners, newbies, and mountain challenge lovers – welcome back to a new chapter on my blog!

Usually, this space is all about sharing tips and motivation for those taking their first steps into running and trail running, helping beginners push through obstacles and hit their goals. But a couple of times a year, I’ve decided to switch gears and share stories from some of the most memorable races I’ve run.

And I wanted to kick off this section with my experience at the Gran Trail de Peñalara 2024, better known as the GTP – a race that has a very special place in my heart.

Running ultras like the GTP, with its brutal weather and physical challenges, is a lot like navigating today’s crazy world of global trade and geopolitics: both require long-term vision, consistency, and rock-solid determination to push through storms – whether it’s rain and wind in the mountains or tariffs on the world stage.

In this article, I’ll take you through my story of this one-of-a-kind race, held under insanely tough conditions that tested not just my legs but also my mind.

This is pure heart: my personal adventure battling nightmare weather, being blown away by a goosebump-worthy act of sportsmanship, and rocking out with a group of trail “rockers” who totally saved my day.

So lace up your trail shoes and come with me up into the mountains of Madrid to discover why the GTP is such a mind-blowing experience!

What’s the GTP?

The Gran Trail de Peñalara, or simply GTP, is one of Spain’s most iconic and legendary ultra trails. Since 2010 it’s been held in the heart of the Sierra de Guadarrama National Park (between Madrid and Segovia), organized by the historic Real Sociedad Española de Alpinismo Peñalara (RSEA Peñalara).

For trail runners in Spain, this race is a true classic – a must-do for anyone who loves long mountain ultras. And by the way, 2025 marked its 15th anniversary.

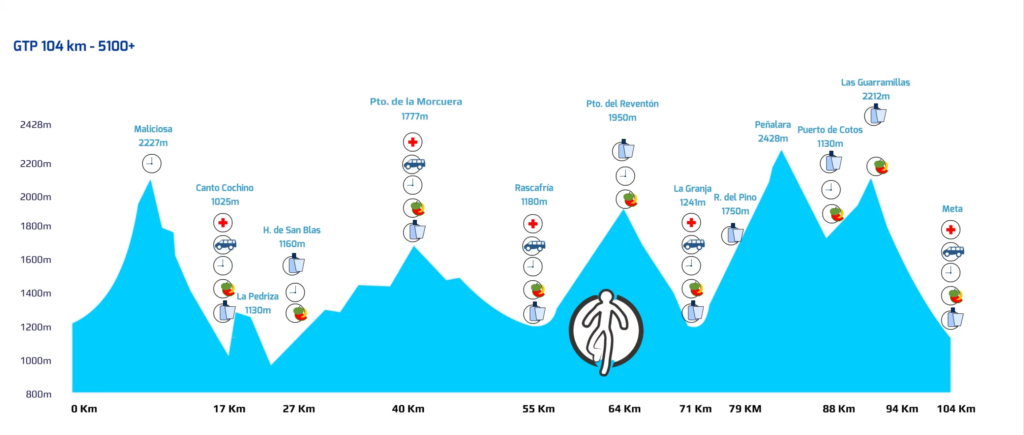

The traditional course is pure mountain magic, linking up some of the wildest and most spectacular corners of the Central System:

- The start in Navacerrada

- The climb to the ridges of La Maliciosa

- The granite chaos of La Pedriza and the “caldera” of La Hoya de San Blas

- The mythical Puerto de la Morcuera

- The forests around Rascafría

- The brutal climb to Puerto del Reventón

- The technical (and sketchy) ridge of Risco de Claveles

- The summit of Peñalara (2,428 m) – the rooftop of Madrid

- And the legendary finish via Bola del Mundo, back to Navacerrada after passing through La Barranca.

All in all, 104 km and 5,100 m of elevation gain, mixing technical singletrack, forest roads, alpine ridges, and quad-burning descents.

But the GTP isn’t just a tough race. It’s a race with a soul. Here, camaraderie, respect for the mountain, and the pure spirit of trail running are alive in every step. And you’re never really alone – more than 400 volunteers make it possible every year, cheering under sun, rain, or storms.

On top of that, the GTP is part of the official trail circuits that hand out:

- UTMB Index 100K, making it a qualifier for the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc (Chamonix)

- ITRA points, useful for other international ultras and the global mountain running circuit

The full GTP weekend also includes several distances, so there’s something for everyone:

- GTP 104K (the queen race – the one this story is all about)

- TP60K (Trail Peñalara – 61 km with 2,700 m+)

- Cross Nocturno (11 km night race with 450 m+)

If you’re curious to learn more about the race and its roots, here’s a cool interview on the “Contador de kms” podcast with one of the organizers. (in spanish)

GTP 2024: An Odyssey in the Storm

The Gran Trail Peñalara (GTP) 2024, held in October in the Sierra de Guadarrama, was my fourth attempt at this beast of an ultra. I’d crossed the finish line once (2023), DNF’d twice (2018 with heat stroke, 2022 thanks to brutal weather), and this time I was going alone, without my usual partners, Mario and Javi.

What was supposed to be 104 km with 5,100 m+ got cut down to 90 km and 4,000 m+ because of apocalyptic weather. And honestly, it turned into one of the toughest, most epic editions anyone can remember. Two things defined this year’s race: 1. A climate straight out of the end of the world. 2. A finish-line gesture that sums up the true spirit of trail running.

Fighting the Elements

Even days before the race, we knew the forecast was grim. A heavy storm was moving in over Madrid and the mountains.

During the pre-race briefing (streamed on Instagram two days before the start), the organizers already dropped the bomb: this year we’d have two drop-bag stations instead of just one – Rascafría plus an extra in La Granja. That meant completely rethinking logistics, bringing way more spare gear, and basically preparing for a cold, soaking battle.

And wow, they weren’t kidding. Later race reports even called this the toughest edition ever. The folks at carrerasdemontana.com straight-up wrote that GTP 2024 was “the hardest one ever remembered in Navacerrada.”

By Friday evening, just six hours before the start, the organizers had to redesign the route, chopping off the iconic climbs to Risco de Claveles, Peñalara, and Bola del Mundo. Safety first, both for runners and volunteers.

The new plan: 90 km, 4,000 m+, and a midnight start to dodge the worst of the storm. Spoiler: the storm caught us anyway.

We got slammed with relentless rain, insane winds, and thick fog where you couldn’t see more than 100 meters ahead. Pure chaos.

A Finish-Line Gesture for the Ages

But the real magic of GTP 2024 happened at the finish line. In the men’s race, Javi González was leading after 10+ hours of battling through the storm. By the climb to Navacerrada he had a solid 2:30 lead, the win practically in his pocket. But fate had other plans: on the final descent (the infamous Camino de la Tubería), with fog, rain, and exhaustion messing with him, he missed a turn and lost the lead.

So Agustín Luján was the first to hit the finishing carpet in Navacerrada. But instead of crossing the line, he grabbed the mic from the speaker (Contador de km himself) and, in front of a drenched but roaring crowd, declared: “Javi is the real winner. He dropped me on the climb to Navacerrada, and I don’t know where he got lost. I won’t cross until he arrives, because he’s the true first.”

Luján then waited 12 minutes in the pouring rain, standing next to a sponsor’s banner while the crowd went wild chanting both their names.

When Javi finally arrived (with third-place runner Jesús Bermejo by his side), Agustín insisted they all cross together. Javi resisted, saying “getting lost is part of trail running,” but Agustín and Jesús wouldn’t hear it. So the three of them crossed the line side by side in 10h19, greeted by a roar like a stadium crowd. Javi, in tears, said afterward: “This is bigger than a victory. Trail values come before everything.” Agustín, as humble as ever, just shrugged: “I’m not getting rich with this. I just want to keep running with friends for years to come.”

The moment went viral. Media like El País, Marca, Antena 3, and Runner’s World all picked it up, calling it “the sports moment of the year” and “an example of sportsmanship every kid should see.”

IT WAS....

TRAIL HISTORY IN THE MAKING.

My Inside Story of GTP 2024

Preparing: Training, Mountains, and Solitude

This was my fourth time lining up at the GTP, and I knew it was no joke. With one finish and two DNFs on my record, I prepped hard in the months leading up to it. What made it tougher this time was that I’d be racing alone – no Mario, no Javi, not even Román, the usual gang of crazies.

So, I prepared thoroughly, and the months leading up to it were a festival of training sessions and participation in preliminary races to get in shape. The actual preparation began in earnest in May (five months before the race), when I designed the training plan and, above all, started to mentally prepare myself to face the challenge alone. One of the things I also began to prepare during that month was the race logistics, which I believe was fundamental to achieving success in the event.

When it came to logistics, since I was going to be on my own, I decided to change the routine from previous years. Back then, we’d go straight from Madrid to Navacerrada about three hours before the race, and once it was over (after more than 22 or 23 hours), we’d head straight back to Madrid. That always added a bit of stress, especially in the hours leading up to the start. So this year I decided to switch things up and booked a hotel right in Navacerrada. That way, I arrived at the hotel on race day around 3 p.m., had time to rest, calmly get everything ready, and head to the start line without rushing. And the next day, after crossing the finish line, I just had to walk 1 km back to the hotel, take a shower, and crash until the next morning.

Another key factor in tackling the race was both the training plan I put together and the choice of the races I did beforehand. I designed a plan with two different peaks of form (one in June–July and the other for the race itself, in early October), with a mid-phase of maintenance in between (July–August). As I mentioned, I kicked things off in May, five months out, and during the first month and a half I focused on tough short-distance sessions (about 10–15K) with vertical climbs of at least +1000 meters every time I went out.

Para alcanzar el primer pico de forma (unos 3-4 meses antes de la carrera) escogí correr dos carreras del circuito UTMB (y así aprovechaba y conseguía los famosos running stones tan necesarios para el UTMB Mont-Blanc). De manera que la primera semana de junio corrí la UTMB Tenerife Bluetrail de 73K y 3.000+ (https://tenerife.utmb.world/races/tbt-100K) . Ésta vez, la carrera si la corrimos juntos el “cuarteto de locos”: Javi, Mario, Román y yo. De hecho, fue la única carrera del año que pudimos hacer juntos. Una vez hecho Tenerife continué con los mismos entrenos para poder alcanzar el primer pico de forma a mediados de julio.

And so, in mid-July, I ran another race in the UTMB circuit, the Eiger Ultra Trail, held in Grindelwald, Switzerland, right in the heart of the Swiss Alps. This time, I ran the 37K version with 2,500 meters of elevation gain, which, although it might seem easy, includes two tough climbs to peaks above 2,000 meters. For this race, I decided to run it alone to start getting used to the mental challenge of spending hours and hours in solitude, preparing for what lay ahead. Although my two great training friends in Switzerland, Alberto and Mario, were running the 100K, so at least we were "together in spirit."

After completing those two races and reaching a good peak in fitness, it was time to dial things back and focus on maintaining that level through July and August. Then, from mid-August (with a month and a half left before the race), I returned to intense training to reach 120% of my fitness level for the second week of October (the race date).

Upon returning from my Swiss training sessions in mid-August, I faced an additional challenge. My training partner, who had been with me through hours and hours and hours of training, Alberto, had to “drop out.” He had been dealing with an injury since the start of the year, which forced him to withdraw from the Eiger, and by the end of the summer, he couldn’t go on and wisely decided to stop. In fact, he ended up needing surgery in December. So, with just a month and a half left before the race, I found myself alone to tackle the toughest training sessions. At the time, it was hard to process and find the motivation, but looking back, it was actually a great way to train and prepare for the solitude I would face on race day.

So, I dove into my training, which I designed differently from the first part of the preparation. This time, I decided to increase the distance in kilometers while maintaining an average elevation gain of at least 1,000 meters per session, but running more and cresting well above 1,600 meters of altitude at a minimum to build race pace and increase aerobic workload for greater endurance. Above all, I extended my outings to a minimum of 4-5 hours.

And so I continued until the week before the race, when I reduced my training load and focused on eating and hydrating well, while preparing all the necessary logistics.

First Half of the Race: Navacerrada to Rascafría

The start in Navacerrada

The GTP usually starts at 11:30 PM from Friday to Saturday. However, in this case, as we’ve already mentioned, the organization decided to delay the start by 30 minutes to midnight on Saturday to avoid the bad weather conditions that were present.

The start of the GTP is always spectacular, set to the anthem of the RSEA Peñalara, but this time it was something special. Just one minute before the start, the organization decided to hold a minute of silence in memory of José Luis García Fernández (Pepelu), a runner and volunteer at nearly every edition of the GTP, who had passed away a few months earlier (in July) while competing in the Desafío Somiedo. It was a deeply moving gesture by the organization, and truly much appreciated.

Night Section: Navacerrada → La Maliciosa → La Morcuera

The stretch from Navacerrada to La Morcuera was hell.

We started on the stretch from Navacerrada to La Morcuera, which was an absolute hell. This year, going alone, I decided to change my race strategy and try to complete the first half of the race (up to Rascafría) as quickly as possible to avoid worrying about control point cutoffs and have enough margin to “enjoy” the race.

So, I decided right from the start to position myself in the middle of the pack and go out strong to complete the first stretch (the climb to La Maliciosa and descent to Cantocochino) as quickly as possible. This is a familiar stretch from my training sessions in the Madrid mountains, so I know it perfectly and understand where I can “push” and where I can’t. The climb to La Maliciosa is a demanding 10 km ascent (from the start in Navacerrada) with over 1,000 meters of elevation gain. The strategy was clear: go out strong and climb La Maliciosa quickly. And boy, did I do it! I nailed the climb in 1:40, a time that made me puff out my chest, though the weather was no joke. During the climb, we had rain and cold wind, coupled with thick fog at the summit of La Maliciosa, which stayed with us for much of the descent as well.

While the climb to La Maliciosa was fast but tough due to the weather conditions, the descent to Cantocochino was even worse. The first part of the descent from La Maliciosa is one of the most technical sections of the race. We faced harsh conditions with rain, cold crosswinds pushing you sideways, and, above all, thick fog where you could barely see beyond the beam of your headlamp and could hardly make out the runner ahead. On top of that, because of the fast climb I’d done, I tackled the descent within a group of runners who typically jog or even run this section technically. So, I had no choice but to throw myself into the descent, using my trekking poles for support and trying to jog or run while sticking close to the runner in front of me, no matter what. And that’s what I did. Luckily, this is one of the descents I’ve trained the most for in this race, which helped me avoid losing too much time and maintain the buffer I’d gained on the climb.

In summary, the descent from La Mali (as we affectionately call La Maliciosa) was insane: barely any visibility, with rain and wind lashing, and terrain that was pure risk.

But I reached Cantocochino in 3:25, almost 35 minutes ahead of the cutoff. Objective achieved.

At the aid station, I took advantage of the time buffer I had gained to “lose a bit of time” removing the thermal layer I was wearing (which had saved my life on La Maliciosa) and switching to a thinner one, anticipating the temperature change I knew was coming in the next stage of the race: La Hoya de San Blas.

And indeed, things got complicated in La Hoya San Blas. The weather took a radical turn: from rain and fog we moved to heat with humidity and fog. Although the rain stopped, the fog was still there, and the ascent and descent of this section were a torment. This is, without a doubt, one of the most technical stretches of the GTP, along with the descent of La Mali."

This is not the first time La Hoya has given me trouble; in fact, my first withdrawal from this race was here due to heatstroke.

It is a valley located in the Sierra de Guadarrama, between La Pedriza and Cuerda Larga, about 15 km long with an elevation gain of around +700 m. It has a short but very intense climb and a long, technical descent. It is not one of the hardest areas of the GTP (although it may well be the most technical section of the entire race), but it is a place where traditionally it gets very hot, and I always struggle there (my body doesn’t handle sudden temperature changes very well, and above all, it doesn’t ‘work’ properly in heat and humidity).

Once I had finished the long technical descent, with the fog accompanying us at all times, in the flat section near the La Hoya aid station, one of the most spectacular moments of the race happened to me.

There, in the middle of the night, with thick fog all around and in the midst of my suffering after almost 5 hours and 30 minutes of racing, I suddenly lifted my head, and my headlamp lit up right in front of me an impressive image: a white horse grazing in the middle of the fog, barely five meters away from me.

The sight was simply spectacular!!!"

"And so I reached the La Hoya aid station, from where the climb to La Morcuera awaited me, which I had to reach before 09:00 hours of racing (cut-off time)

I left this aid station completely exhausted. The previous stretch had beaten me down (marked by the stress of the fog and the technical descent), so I tried to join two runners who were together to follow their pace. But no, my legs just couldn’t give any more. Luckily, it started to rain and cool down, and that gave me some relief. I cheered up, started jogging, and little by little, I began to feel better.

The climb to La Morcuera is gentler than La Maliciosa, but endless. It covers about 12 kilometers with 600 m of elevation gain (this year it was 13, since due to the bad weather at La Morcuera, the aid station had to be moved 1 km further on from where it is usually set, at the top of the pass). Right from the start, it began to rain harder and harder. Then things got worse: a torrential downpour drenched me to the bone, and combined with the fog that still lingered, it barely let you see beyond the beam of your headlamp.

At this moment, I made one of the big mistakes of the race. Among the mandatory gear required by the organization—and which they checked we were carrying in our backpack at the start—was a waterproof jacket of at least 10K, waterproof pants, and gloves. Well, I had packed all that mandatory gear in my backpack, and in addition, my Bonatti rain jacket, which I usually train with and especially like because it also covers the backpack. When it started raining, I put on the Bonatti jacket; but when the downpour began, out of pure laziness (I didn’t feel like stopping in the middle of the deluge, taking off one jacket, opening the backpack and pulling out the other 10K Cimalp jacket, waterproof pants, and gloves), I decided to keep going as I was. That turned out to be a huge mistake, which nearly ruined my race. Halfway up the climb, I was completely soaked, and the extra kilometer we had to cover at the top of La Morcuera to reach the aid station was a nightmare under the pouring rain that was pounding us.

I reached the La Morcuera aid station soaked and freezing, but with a time of 08:20, which gave me a 40-minute margin over the cut-off.

There, a volunteer saved my life with a cup of hot coffee she gave me, which brought me back to life. Dawn was already breaking, and with the first light of day, I took advantage of the margin I had over the cut-off time and stayed about 30 minutes in the aid station tent, waiting for the downpour to ease.

I took the opportunity to change clothes and put on dry gear that I had in my backpack to face the descent to Rascafría. Luckily, I had dry clothes with me (a lesson learned from the 2022 GTP race, in which I dropped out due to the weather conditions and, among other things, for not having dry clothes in my backpack after a downpour hit us on the climb up El Reventón). So this time, I had made sure to pack clothes inside plastic bags in my backpack to guarantee that no matter how much it rained and the backpack got wet, the clothes inside would stay dry. Without a doubt, this was one of the actions that saved my race.

The Dawn: From Morcuera to Rascafría

I recovered my strength and, with dry clothes, I faced one of the parts I enjoy the most in the race: the descent from La Morcuera to Rascafría. It is a descent of about 14 km along a trail without technical sections, where you can really let loose; although you do need strong legs for it, because if you reach this stretch already worn out, the descent can turn into hell.

However, this time the descent was not as good as in previous years. It kept raining the entire time (though without fog now and with daylight), and although I was already wearing the Cimalp rain jacket, halfway down my hands were soaked and numb with cold, and that’s how we continued until Rascafría

However, the descent wasn’t all that bad. I left the La Morcuera aid station with a 10-minute margin over the cut-off (after the 30-minute stop) and reached Rascafría with almost a 50-minute margin over the cut-off.

But in Rascafría, I hit rock bottom mentally. I was on the verge of dropping out. The harsh conditions of the night—with wind, cold, fog, and heavy rain, at times even torrential downpours—had taken such a toll on me mentally and with so much stress that upon reaching Rascafría I suffered a major breakdown. And even more so when, upon arriving at the aid station, I asked a volunteer and he told me that the weather forecast was for the rain and cold to continue until 2 in the afternoon… and it was only 10:30 in the morning!!!!"

My mental crash was so severe that I even sent a WhatsApp message to my group of friends and runners from ‘Casa de Campo,’ telling them that I was dropping out, that the night had been extremely tough and the weather conditions were awful.

But then, suddenly, my mind clicked, and I drew on years of experience in these races. From experience, you know that during these races there are ups and downs, and often success depends on how you manage those low moments. It may sound trivial, but sending that WhatsApp message to my friends, who share with me so many kilometers of training, was liberating. It was a way to shed all the bad vibes from having run for 10 hours and 30 minutes in rain, cold, and fog. Suddenly, I drew on experience and changed my mindset.

I knew from experience that in these races you always have a mental low point that you have to know how to manage and have the calm to understand that, with patience and little by little, the good feelings will return, and above all, that every kilometer completed was one less to the finish line

I calmed down, grabbed the life bag I had in Rascafría, changed clothes, and prepared myself for the second part of the race. Little by little, I recovered mentally, and after eating something, I started talking with one of the runners I had met on the climb to La Morcuera and the descent to Rascafría. Together, we left the aid station heading toward Cotos—this time fully equipped to endure the rain and bad weather, wearing waterproof pants!!!

In total, between the 30 minutes ‘lost’ in La Morcuera and the 40 minutes ‘lost’ in Rascafría, I had approximately an hour delay compared to the time I had planned. I had prepared to finish in 22 hours, and considering that the race had been shortened by 15 km and 1500+ meters of elevation gain, I estimated finishing about 3 hours faster. So my goal was to try to finish in around 19 hours. That said, I left Rascafría with 1 hour delay compared to my goal (which was equivalent to finishing the regular GTP in 23 hours)

Second part of the race: From Rascafría to the finish (Navacerrada)

The Morning: From Rascafría to Cotos

I left Rascafría heading towards Puerto del Reventón around 11 in the morning (about 10 minutes before they closed it), knowing that the rain would continue until 2 in the afternoon and the weather would remain bad. The organizers, however, gave us a break: they had cut the ascent to Peñalara and Bola del Mundo due to weather conditions, so what remained was ‘a bit easier.’ Mentally, I was once again ready to grit my teeth and push to the finish, even though I had already endured 11 hours of hardship. The rain kept falling, but I was already in ‘hold on and keep going’ mode. I had 35 km left to the finish and only about 1800 meters of elevation gain.

The first part from Rascafría to Cotos was a stretch of about 20 km with 1000+ meters of elevation gain, while the second part from Cotos to the finish (Navacerrada) was about 15 km with around 800 meters of elevation gain.

The cut in the ascent to Reventón was a relief. We climbed up to halfway up the pass, and then came a 5 km descent that gave me new life, during which I went all out, ‘giving it my all,’ allowing me to start reducing the time I was behind my goal. That said, whatever goes down must come up, and I knew sooner or later I would have to face that 1000+ meter climb up to Cotos

During the descent, I began to feel my body responding again, and just as we started the long climb to Cotos, something magical happened. On a tough stretch, along a trail that was starting to challenge me, I heard two guys behind me talking about music. The words ‘Extremoduro,’ ‘Metallica,’ and ‘AC/DC’ hit me like a lightning bolt. That was my kind of thing! I decided to slow down, let myself fall back, and stick with them. Best decision ever.

I joined them, and it was like finding an oasis in the desert.

The first part of the climb was an absolute high: we talked about the great rock classics and trail running—a great mix! Honestly, most of the ascent went by as we chatted about the hits of Extremoduro, Platero y Tú, Barricada, Rosendo, and the Metallica concerts in Madrid that summer, even about the Iron Maiden concert scheduled for July the following year. In fact, I ended up running almost the entire way to the finish in Navacerrada with one of them

But the last 4-5 km before Cotos were hell

We started a climb on a technical trail that was quite tough. The slope was like a wall, and the drizzle kept wearing me down. Honestly, this climbing section finished me off and wiped out the few remaining forces I had. It was a stretch of about 4-5 km with nearly 1000 meters of elevation gain.

And then, after finishing one of the hardest sections, something epic happened. Upon reaching the summit, the weather suddenly changed, and we saw rays of sunshine breaking through. Then one of the guys I was with, emulating the song 'Pepe Botika' by Extremoduro, said... 'A clearing opened among the clouds.' Without hesitation, I followed: 'We’ve seen the sun again, like two common prisoners on a prison rooftop.' What a moment

Honestly, these guys saved my race. They didn’t just lift my spirits but reminded me why I love trail running: it’s not just about running, it’s about sharing moments with strangers, helping each other out, even when you’re literally exhausted.

During the final part of the climb to Cotos, I also shared a few kilometers with a very nice guy who told me he lived in Andorra and worked as a ski instructor in winter. Together, we did the last 4 km to the Cotos aid station where his family was waiting for him.

And so, I arrived at the Cotos aid station, at kilometer 75 of the race, with only 15 km left to the finish and just one climb of about 800+ meters remaining.

Everything was looking very good, but as it always happens in these kinds of races, things got a bit complicated. This time it wasn’t the weather or mental struggles; it was my stomach playing tricks on me again. And it wasn’t the first time this had happened...

The Afternoon: From Cotos to the Finish (Navacerrada)

I arrived at the Cotos aid station completely exhausted.

The last climb of over 1000 meters had completely drained me. I tried to drink a hot broth to regain strength, but my stomach said ‘enough.’ Just after leaving the aid station, I vomited everything. It was clear that the effort of the climb had taken its toll. From that point on, my stomach shut down: everything I tried to take in, whether liquid or solid, came right back up.

Then came a descent that gave me a breather. I caught my breath a bit and reunited with one of the guys I had been chatting about rock music with during the race. A very nice girl also joined us, cheering us up and sharing stories from other races she had run. Together, we did a 4-5 km descent that gave us new energy. I was cautious because my stomach was still rebellious, but I managed to cut a few minutes off the delay I had accumulated.

But the joy didn’t last long, and what goes down must come up. At the end of the descent, we faced the penultimate climb of the day to the Puerto de Navacerrada: about 4 km with 600+ meters of elevation gain. Right at the start, my stomach said “enough.” I vomited everything I had tried to drink on the descent. I faced that climb completely empty, unable to hold even water. I fell behind the group, and on the way I vomited again. I was in bad shape, weak, and the climb felt endless. Many runners passed me, but I was only thinking about pushing forward with whatever I had left.

Upon reaching the Puerto de Navacerrada, almost exhausted, the weather turned even worse: rain, wind, and fog

At that moment, I looked up and couldn’t even see Bola del Mundo (where we were supposed to be passing). I was immensely grateful for the organizers’ decision, as it would have been absolute madness to try to cross Risco de Claves, Peñalara, and Bola del Mundo in such terrible weather at the summit.

At the aid station, I made another key decision: not to stop (even against advice). I had my water bottles full (though I couldn’t drink), and there were only 9 km left to the finish. The next part included a small climb of 200+ meters and then a descent along the Camino de la Tubería, a trail I know by heart because I train there almost every time I go to the Sierra de Madrid.

On that small climb from Navacerrada, I started to feel a little better. I caught up with the friend I’d been talking rock with, and we continued together. Not stopping at the aid station was one of the best decisions I made. With my stomach in revolt, stopping would have just cost me time.

When we reached the Camino de la Tubería, I felt right at home. I knew every stone, every turn. I had been racing for 18 hours, but I had made up much of the time lost in the first half of the race.

I launched into the technical descent with an ambitious goal: to finish in under 19 hours. I knew it was tough since the descent from the start to the finish in Navacerrada usually takes between 1:15 and 1:30. The two of us went down together, pushing hard.

Before reaching the last aid station at La Barranca, we exited onto a forest track. I was feeling good, so I told my running partner that I was going to push ahead. The rain had returned, but I didn’t stop at La Barranca. I just wanted to get there. I ran the descent, although my stomach started giving me bad signals again. Just before entering the town of Navacerrada, I had to stop and vomit once more.

I ran the last 2 km in the village under the rain.

I crossed the finish line as always: cheering the crowd, waving, and shouting at the top of my lungs. What a high after so much suffering!

In the end, I crossed the finish line in 19:11, within the goal I had set for myself. If the GTP had been the original course, it would have taken about 22 hours.

Once I reached the finish line, I asked the speaker's microphone and said a few words to thank the volunteers. They endured a horrible day of wind, rain, and cold, but at every aid station, they greeted us with a smile, offering coffee, hot broth, and encouragement. They are the true heroes of trail running.

Once at the finish line, I met up with the friend I had run with for half the race and the girl who had accompanied us since Cotos. We congratulated each other and shared an epic hug.

That is the spirit of trail running: sharing the suffering and the joy.

I finished my second GTP, this time alone and in crazy weather conditions.

I overcame the cold, rain, fog, and my own mind. Physically, I had no problems, but the stomach issues are something I need to look into. It’s not the first time it has happened, so I’ll have to adjust my nutrition and listen to my body better to avoid these episodes.

What an experience, what a race, what everything!

The GTP has once again taught me that trail running is much more than just running:

It’s about enduring, sharing, and surpassing your own limits.

Would I do it again? Of course! But with my rain pants on from the start.

GTP 2024 Links

And to finish this post, I’m also sharing two really cool videos. The first one was recorded from inside the race by a "famous runner." The great Richar Tejedor (https://www.instagram.com/richar/), collaborator of the Find your Everest podcast of which I am a loyal follower and club member.

And the second one, the official race video in which you can see the weather conditions we faced and the great epic moment at the end of the race.

And remember ..... YOU'LL NEVER RUN ALONE!!

And if you are interested in training plans for this type of race or others, all you have to do is visit our “Contact” page (https://tradeandtrail.net/en/contacto) and write to us.

Link excdhange is nothing elkse but it is just placing the other person’s webog link on your

page at suitable place and othher person will also do same

for you.

Hello lads!

I came across a 143 useful platform that I think you should check out.

This resource is packed with a lot of useful information that you might find valuable.

It has everything you could possibly need, so be sure to give it a visit!

[url=https://jealouscomputers.com/the-4-most-read-books-in-2021/]https://jealouscomputers.com/the-4-most-read-books-in-2021/[/url]

Furthermore remember not to forget, guys, — you always may inside this particular article discover answers for the most tangled questions. Our team tried to present the complete content via the most easy-to-grasp way.